Obviousness is a very common reason for rejection.

A grant of patent without a single rejection is quite uncommon. One of the reason is that most applicants want to claim broadest possible for the greatest protection of law.

Broadening the scope of claims.

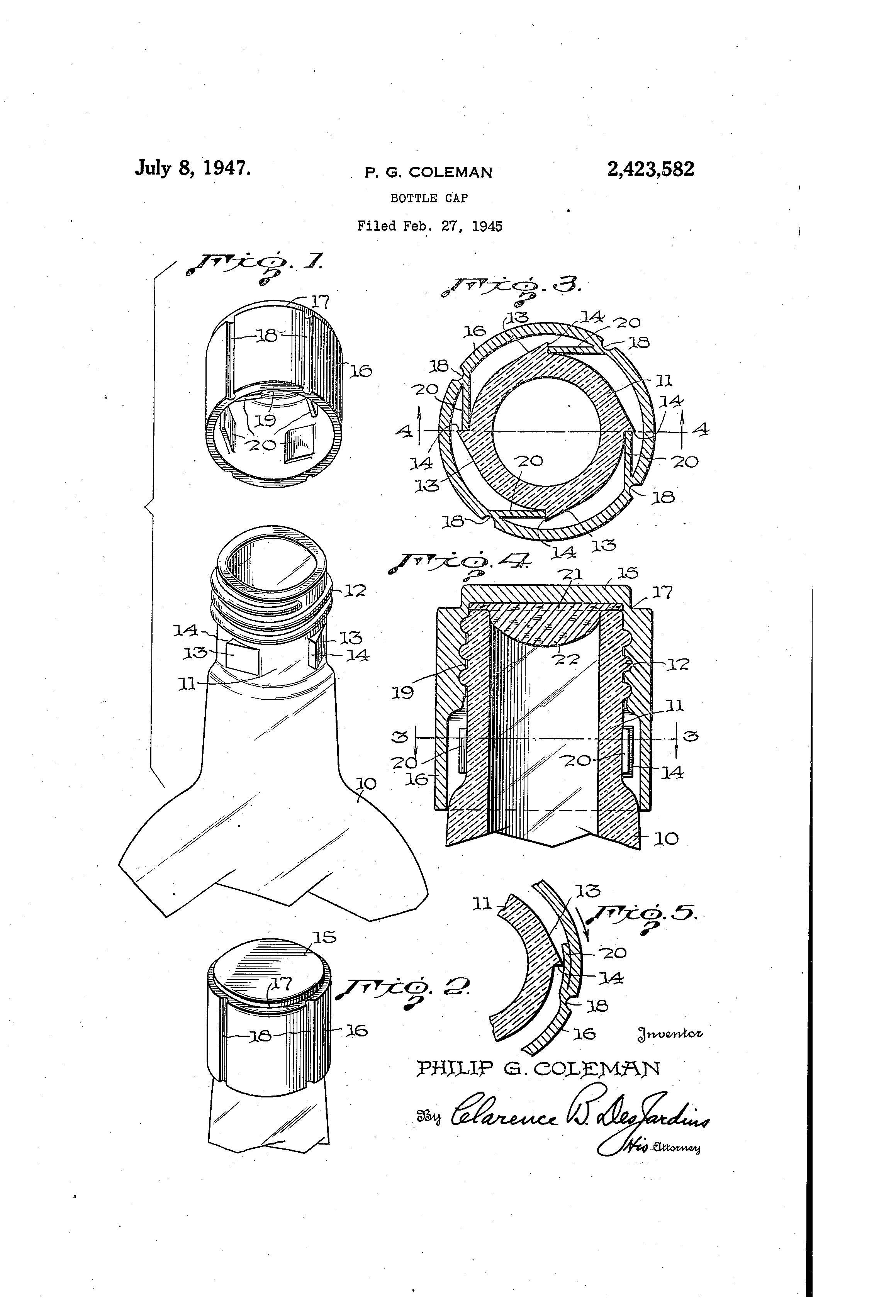

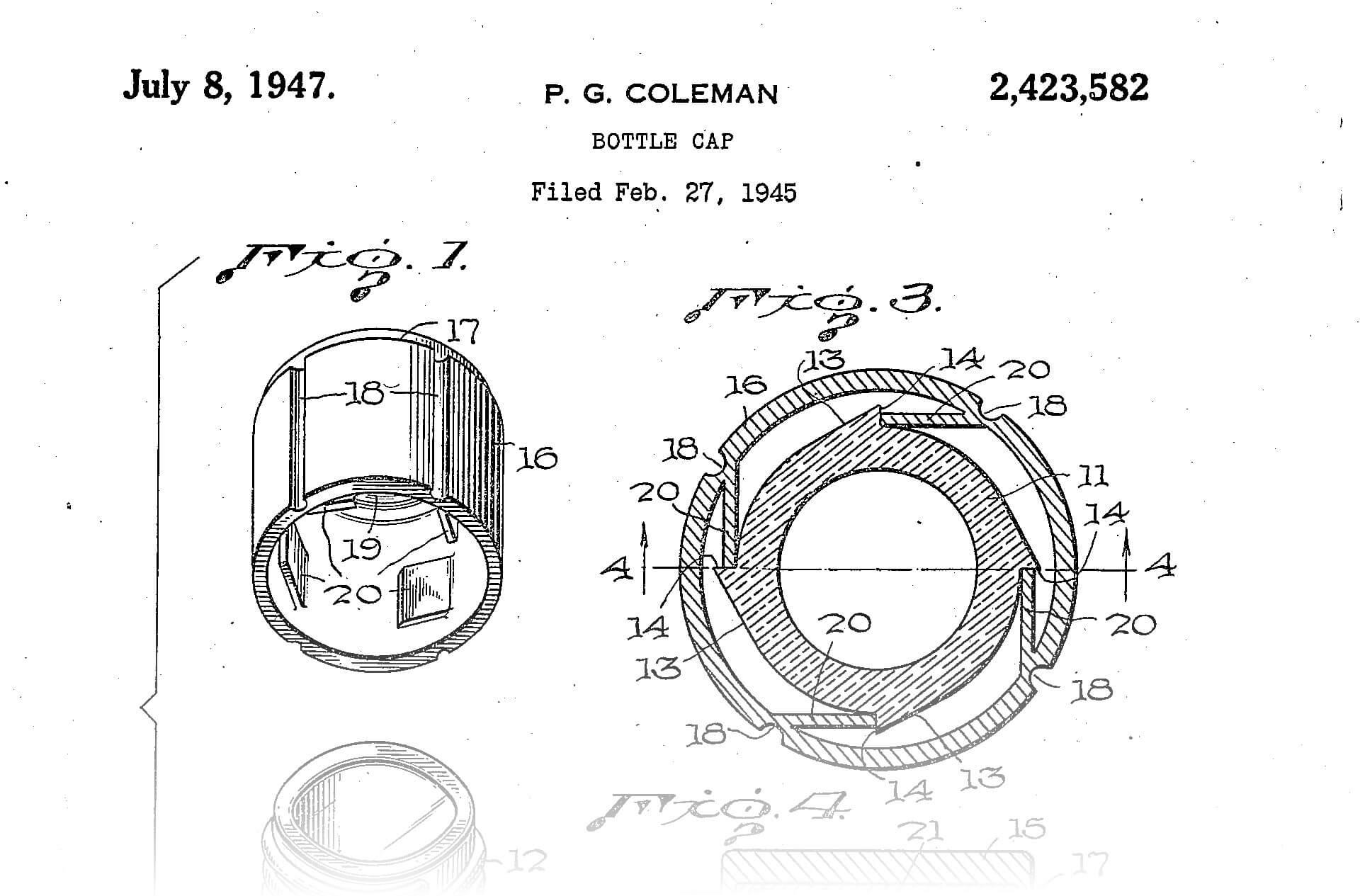

To maximize the scope of your claim, you don’t want to include unnecessary details in your claim. Let’s take a look at an example (from a real patent). You don’t have to read it through, just scheme.

[an excerpt from US8143982B1, bold added]

1. An accessory unit, comprising:

a hinge span, the hinge span including a first magnetic element suitable for magnetic attachment to a host unit having a display; and

a flap portion pivotally connected to the hinge span, the flap portion comprising:

a plurality of segments all but one of which are substantially the same size and wherein one segment is wider than the other segments, wherein each segment includes a pocket that is about the same size as the corresponding segment,

a rigid insert incorporated into each pocket, the rigid insert providing support for the associated segment, and

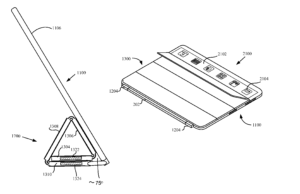

a folding region between each of the segments arranged to allow the plurality of segments to fold with respect to each other, wherein a first segment is located at a first end of the flap at the hinge span and includes a magnetically attractable element and wherein a second segment is located at a second end of the flap opposite the first end and includes a plurality of magnets, wherein in a first folded configuration the flap portion forms a triangular structure when the first and second segments are folded one atop the other such that at least one of the magnets in the second segment magnetically attract the magnetically attractable element in the first segment, wherein the first and second segments that are folded one atop the other and magnetically attached to each other form one side of the triangular structure that is about equal in width to a second side of the triangular structure each of which is narrower than a third side of the triangular structure.

[end of claim 1]

What’s claimed?

By looking only at highlighted words, you can figure out that it has two main components, a hinge span and a flap portion, and the flap portion has three sub-components, a plurality of segments, a rigid insert for each segment, and a folding region between each of the segments.

What do you make out of it? Well, it’s iPad Smart Cover by Apple.

Let’s look into the details.

A hinge span is described as follows: including a first magnetic element suitable for magnetic attachment to a host unit having a display.

It doesn’t say a magnet or a tablet PC. Instead, it says a magnetic element suitable for magnetic attachment and a unit having a display, respectively. If it said a magnet, someone can make a cover with a lodestone instead of a magnet and avoid infringement. The same thing goes to the tablet PC.

But, why not just an element suitable for attachment? I think that would be the track which leads to the obviousness trap. Granted it would expand the scope, it also eliminates an outstanding element from the invention. Every cover has some element for attachment.

On a side note,

what about a unit having a display? Why not a unit having a flat surface? Well, Apple is an electronics company, and it probably wouldn’t make a cover for your photo frame. In that sense, a display pretty much is everything that needs to be covered in Apple’s patent.

Infusing non-obvious elements into claims.

Skipping forward to the bulky section, a folding region, can you guess why in the world it is so long? Well, you guess it’s important, right?

This is the section that makes this cover distinct from any other cover design within people’s mind (at the time of invention, of course). It describes how the segments of a cover fold and magnetically bind together to form a rigid stand that can support a host unit. So, you have to describe it fully.

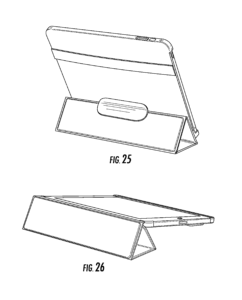

By the way, a cover that folds into a stand is not an invention by Apple. Search Google Patents “US8960421B1” and you will see a prior patent filed by Incase Designs Corp. that has almost identical folding functionality.

Let’s take a look at a claim by Incase Designs [excerpt from US8960421B1].

1. A cover for an electronic device comprising:

a rectangular front cover comprising first, second, and third panels between a first edge and second edge of the front cover, wherein the first panel is closer to the second edge than the second and third panels, the second panel is between the first and third panels, and the third panel is adjacent the second panel,

between the first and second panels is a first hinge, and

between the second and third panels is a second hinge;

a back cover, coupled to the front cover, which will retain the electronic device in the case; and

[It goes on, but let’s stop here.]

So, a flap portion of Apple patent can’t overcome an obviousness rejection by itself despite the elaborated manner of how segments fold and get attracted together to form a stand; that’s where the magnetic element for attachment comes into play. This magnetic element obsolete a back cover, which is listed in the Incase Designs’ patent claim.

Here’s an important question: if Incase Designs knew a way to make a cover without a back cover, would its claim include the back cover element in the claims?

The fact that Incase Design included the back cover element in the claim supports the non-obviousness of replacing a back cover with a magnetic element.

You can read more about this in “Including an unnecessary element in the claims.”

How to deal with an obviousness rejection.

After a careful thought and drafting an application, you can still get a rejection based on obviousness. In this case, you can try again, or get help from patent attorneys.